Insurance Fraud Costs the U.S. $308.6 Billion Annually

Why is this study important? Insurance fraud is the crime we all pay for, whether through higher premiums,

law enforcement expenses, court costs, and in medical care. The actual cost of insurance fraud on American

citizens is impossible to measure accurately. This report seeks to use the best available data and resources to

accurately estimate the economic damage insurance fraud causes every year in our nation. It is intended to

inform consumers and to guide insurers, law enforcement, insurance regulators, and legislators in the need to

work together to protect consumers from insurance fraud crimes.

Why is the figure so high? In 1995 the Coalition Against Insurance Fraud announced an $80 billion estimate of

insurance fraud in America. That number became the most-cited insurance fraud statistic in the U.S. And while

the 1995 estimate addressed only property & casualty insurance, this report addresses all lines of insurance.

The 1995 estimate was also never updated or adjusted for inflation. Applying an inflation calculator alone

increases the $80 billion figure to $155 billion. The remaining additional $156 billion in estimated insurance

fraud includes the additional lines of insurance, notably healthcare, workers compensation, and life &

disability insurance. Also, in 1995 the internet was in its infancy. Today, the World Wide Web substantially

contributes to new forms of global insurance fraud that impacted the U.S. that did not previously exist.

How was this study conducted? The Coalition Against Insurance Fraud provides this study. When the decision

was made to do the first update in 27 years to the 1995 figure, the Coalition sought input and assistance from

key strategic partners who advised, peer-reviewed, and analyzed this report. These partners include the

International Association of Special Investigation Units, the National Insurance Crime Bureau, the American

Property & Casualty Insurance Association, and the Insurance Information Institute. To ensure a thorough and

independent report, all data collection, analysis, and the study document were prepared by the Colorado

State University Global White Collar Crime Task Force led by Dr. Michael Skiba. The team of PhD candidates at

CSU compiled data from the most reliable sources available for each line of insurance. Such sources include

the FBI, respected trade associations, and regulatory reporting filings. As the study notes, far better data

collection is needed by insurers and governmental agencies to better analyze and quantify the actual cost of

insurance fraud on the American economy.

For more information: Please refer to the Coalition Against Insurance Fraud website: www.insurancefraud.org

or contact the Coalition’s Executive Director Matthew J. Smith, Esq. via [email protected] or by

calling (202) 393-7332.

Study Conducted by:

Colorado State University Global

White Collar Crime Task Force

2022

In partnership with

THE IMPACT OF INSURANCE FRAUD ON

THE U.S. ECONOMY

A report from the Coalition Against Insurance Fraud

Contents

W W W . I N S U R A N C E F R A U D . O R G

I. INTRODUCTION OF THE STUDY

AND THE FRAUD PROBLEM ......................... 2

II. PREVIOUS $80 BILLION COST OF FRAUD

ESTIMATE EXPLAINED .................................. 3

III. METHODOLOGY OF STUDY ..................... 4

IV. SHORTCOMINGS AND

LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY ....................... 5

V. INSURANCE FRAUD BY LINE OF BUSINESS

ANALYSIS ..................................................... 6

Property and Casualty Insurance Fraud. 6

Workers’ Compensation. 13

Premium Fraud. 19

Healthcare Fraud. 23

Medicare and Medicaid. 26

Life Insurance Fraud. 28

Disability Insurance Fraud. 31

Auto Theft. 33

V

I. COMPILATION OF THE LOB’S

INTO A FINAL 2022 COST ........................... 36

VII. STATEMENT ON AUTO THEFT ............... 37

VIII. RECOMMENDATIONS FOR

FUTURE STUDY ........................................... 37

X. APPENDIX ................................................ 38

XI. REFERENCES ........................................... 40

X. CONCLUSION .......................................... 38

OVERVIEW ................................................... 1

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ................................. 41

OVERVIEW

The Coalition Against Insurance Fraud was created in 1993 and remains the nation’s only

consumer advocacy organization devoted to educating and protecting American citizens

from the cost and damage of insurance fraud. The Coalition consists of more than 260

organizations committed to the fight against insurance fraud. These organizations include

federal and state agencies, insurance regulators, legislative and insurance trade

associations, state attorneys general, prosecutors, law enforcement agencies, the majority

of America’s leading insurance carriers across all lines of insurance, and select companies

and law firms assisting in fighting insurance fraud.

In approximately 1995, the Coalition released an estimate of the cost of insurance fraud in

the United States as being $80 billion every year. Unlike other large economic figures, such

as the national debt, the estimate of the cost of insurance fraud is an annualized number,

meaning the financial counter resets at zero and begins anew every January 1st. The $80

billion impact for many years has remained the most often cited insurance fraud statistic

across the nation. Released 27 years ago, the figure has not been updated nor adjusted for

inflation or the advent of new forms of insurance fraud. The time has come to both update

and provide more substantial support for a new defined cost of insurance fraud that

accurately reflects the United States in the 2nd decade of this new millennium.

The Coalition extends its deepest appreciation for the support and contribution of our

partners in this study: the International Association of Special Insurance

Investigators, the American Property & Casualty Insurance Association, the

National Insurance Crime Bureau, and the Insurance Information Institute. This

study also would not have been possible without the support of our members who

support the work done by the Coalition every day. Finally, credit for the work behind this

study goes fully to Dr. Michael Skiba and the research team at the Colorado State

University Global White Collar Crime Task Force. We commend their tireless dedication,

hard work, and excellent analysis upon which this study is firmly based.

2

I. Introduction to the Study and the Fraud Problem

Insurance fraud is one of the most costly and damaging forms of fraud crimes in the

United States and globally. Fraud takes many forms; as scammers change their

methods daily to find new gaps and vulnerabilities. Insurance fraud results in monetary

damage but also causes humanitarian harm. In the area of medical fraud, patients are

often put at great risk and subjected to unnecessary treatments and procedures as a

result of unscrupulous providers attempting to inflate medical billing charges. Thus,

insurance fraud is widespread and has a dangerous impact on our society as a whole.

The purpose of this study is to develop a new cost estimate of the economic impact of

insurance fraud in the United States. Being released in 2022, the estimate represents

the current state of fraud and is intended to assist policymakers, companies, agencies,

government entities, and the public to gain a clearer understanding of the true nature

and scope of the insurance fraud problem. There are no prior studies that have

focused on this level of depth in developing a cost estimate of insurance fraud,

therefore this research endeavor is a truly ground-breaking project. Having a current

cost estimate will undoubtedly assist with creating increased awareness of the fraud

problem which will aid the allocation of resources for more highly focused counter-

fraud strategies.

Colorado State University Global’s White Collar Crime Task Force (WCCTF) is the

research arm spearheading this study, working on behalf of the Coalition Against

Insurance Fraud. The Coalition appreciates the support and assistance of our partners

in this study, the International Association of Special Investigation Units (IASIU), the

American Property & Casualty Insurance Association (APCIA), the National Insurance

Crime Bureau (NICB) and the Insurance Information Institute (III). Many other insurance

carriers, government agencies, non-profit organizations, industry groups, and

individual fraud fighters have all assisted with the development of this project. The

WCCTF consists of dozens of CSUG staff, Ph.D. faculty, researchers, and assistants,

but the primary lead investigators for the purposes of this study were Dr. Greg Koehle,

Landon Palmer, and Allison Blackburn.

This research publication will consist of the following sections:

I. Introduction of the study and the insurance fraud problem.

II. Previous $80 billion cost of fraud estimate explained.

III. Methodology of the study.

IV. Shortcomings and limitations of the study.

3

V. Line of business (LOB) analysis.

a. Current and existing research on the cost of fraud of specific LOBs.

b. Research calculations on the updated cost for the specific LOBs.

c. Compilation of the LOBs into a final 2022 cost estimate

VI. Statement on auto theft.

VII. Recommendations for future studies.

VIII. Conclusion.

IX. Appendix.

X. References.

II. Explanation of the Previous $80 Billion Cost of

Fraud Estimate

The Coalition circulates an estimate of the current cost of fraud as $80 billion annually,

which is the most widely used and popular statistic on insurance fraud cited in multiple

channels daily. Many industry professionals opine that this number is an incredibly

conservative figure and thus the inception of this 2022 study was to develop an entirely

new and up-to-date cost of insurance fraud in the United States. The Coalition

estimates that the $80 billion figure was developed in or around 1995. As a basic first

step in estimating a new cost of fraud, the WCCTF started with the baseline of $80

billion in 1995 and converted that amount into “present-day” dollars.

Using a standard Consumer Price Index (CPI) conversion of $80 billion in 1995 to

January 2022 results in an 81.5% inflation rate, which would convert into a 2022 cost

of fraud in the United States at $145 billion! It is the goal of the WCCTF and this study

to compile a new statistic in a highly methodological manner to present an accurate

2022 cost of insurance fraud.

4

III. Methodology

The WCCTF considered multiple methodological approaches as the foundation of this

study. Consideration was made to conduct the research using a quantitative

methodology, which would involve developing a research instrument in the form of a

survey, which would then be circulated in the insurance industry. The benefit of this

methodology would be real-time results directly from the industry. The WCCTF

explored this option but discovered that this approach would be problematic due to

data privacy concerns. Due to privacy issues with the release of claims, policy, and

fraud information, gathering specific data from carriers and industry groups via a

survey would be incredibly challenging, and yield sub-par data sets. After contacting

several carriers which had data set sources, it was clearly understood by the WCCTF

that the carriers were very resistant to releasing any data outside of their respective

corporate environments, thus making this quantitative methodology, not a viable

research option.

A qualitative methodology was also considered, whereby the researchers would

perform in-depth interviews with industry professionals on fraud cost and

measurement. This would be a very beneficial approach as direct contact and

feedback would be gathered. However, the WCCTF realized that this approach would

also result in the same data and information privacy challenges and therefore would

not be an ideal structure for this research endeavor.

The WCCTF pondered many other research approaches and considered those options

along with the timeframe and resources for this study and thought using available data

sets would be the best option. The WCCTF conducted initial exploratory searches for

several months for available data and existing research on insurance fraud and realized

that there are many data sets, studies, and publications that have already been

performed that can be utilized as the core data points for this current study. Therefore,

the WCCTF decided that the structure of this study will consist of locating, reviewing,

and analyzing currently available research and data sources, in other words, the

WCCTF will not be collecting any “new” data as part of this study.

In each of the Line of Business (LOB) sections, the WCCTF will address the reasoning

behind the choice to utilize specific data as connected to that line of business. The

WCCTF considered and reviewed hundreds of sources to serve this study, but the final

data was chosen based on those sources that were aligned with organizations that had

the highest degree of creditability in the industry and used the most accurate and

effective method of data collection.

5

The WCCTF searched for data within five years of this study date (2016 or newer) to

accurately represent the most current state of the insurance problem. This five-year

range provides robust data as it includes pre-covid data (2016-2020) and covid data

(2020-present). When data was used that was considered somewhat “dated,” the

WCCTF extrapolated the data and metrics and applied a CPI conversion to reflect

today’s cost. This CPI conversion will be explained in detail within the appropriate

sections of the study where it was utilized.

The next phase of the preparation was to identify the lines of business that would be

included in the cost of insurance fraud analysis. After lengthy discussions with the

Coalition and other stakeholders, it was determined that this study would focus on the

following lines of business:

1) Property and Casualty

2) Workers’ Compensation

3) Premium Fraud

4) Healthcare

5) Medicare and Medicaid

6) Life Insurance

7) Disability Insurance

8) Auto Theft

IV. Shortcomings and Limitations of the Study

The WCCTF will be using existing research and data as the core elements of this study,

and accordingly, as with any credible research, there are limitations and shortcomings.

Considering that existing data is being used, the research results are therefore limited

in certain areas as this research was already gathered under pre-set parameters.

Therefore, the team cannot act fluidly and alter data gathering parameters as the study

unfolds, the team must analyze the data that was already captured, which presents

inference and results limitations. However, even with these shortcomings and

limitations, the research team is confident that the results will be credible, sound, and

provide an accurate picture of the current cost of fraud in the United States.

Compiling one cost of insurance fraud for the entire insurance industry across multiple

LOB’s will create a new and fresh picture of the state of insurance fraud. However, it is

understood that each specific insurance company, insurance-related organization,

government agency, industry group, etc. has its own unique place in the insurance

industry. Thus, due to the many unique organizations that exist, certain sections and

LOB’s of this study may not be applicable. It is recommended that insurance

organizations use this study as a baseline and then if needed, modify the findings

revealed in this study to their unique situations.

6

V. Insurance Fraud by Line of Business Analysis

Property and Casualty Insurance Fraud

a) Introduction to the problem:

Property and casualty insurance is defined as a type of insurance that provides

protection for two main areas. First, it protects items that the insured owns. Secondly,

it provides liability coverage as protection for an insured if the insured is found culpable

in an accident and causes property damage or personal injury to another person.

Property insurance is referred to as a “first-party” coverage in that it provides for losses

related to a policyholder’s property, whereas casualty, or liability, insurance is referred

to as a “third-party” coverage, implying it protects a policyholder against the claims of

others. Property and casualty insurance can be written to apply to automobiles,

homes, and businesses. There are three basic types of property loss: 1) loss of or

damage to the article itself, 2) loss of income from the use of the article, and 3) any

extra expense incurred due to the loss of the article. Casualty insurance, which covers

liability losses, are losses that occur as a result of the insured’s interactions with others

or their property. To be liable, the individual must be guilty of negligence or the failure

to use proper care. There are generally three types of liability insurance: 1) general

liability, 2) professional liability, and 3) product liability.

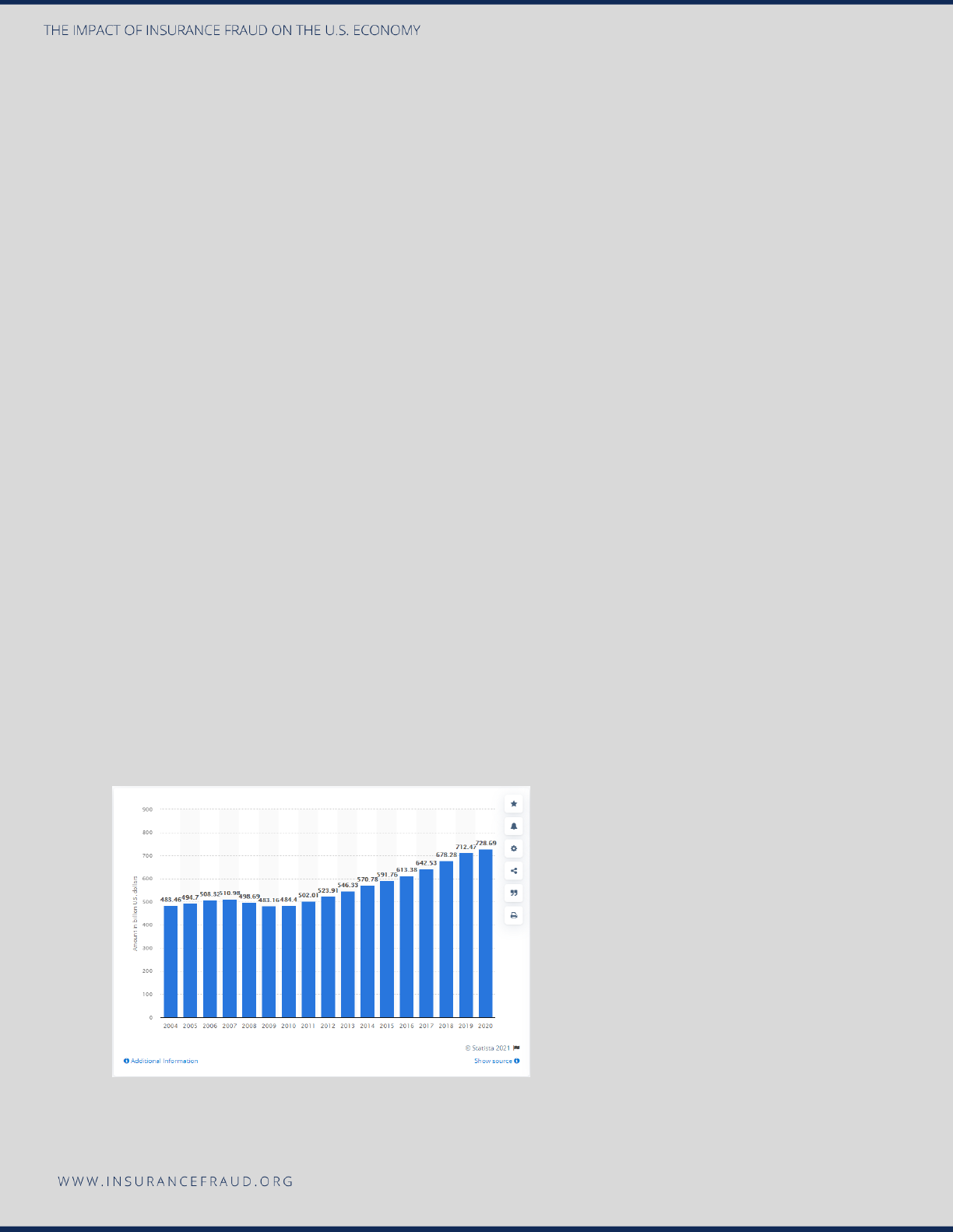

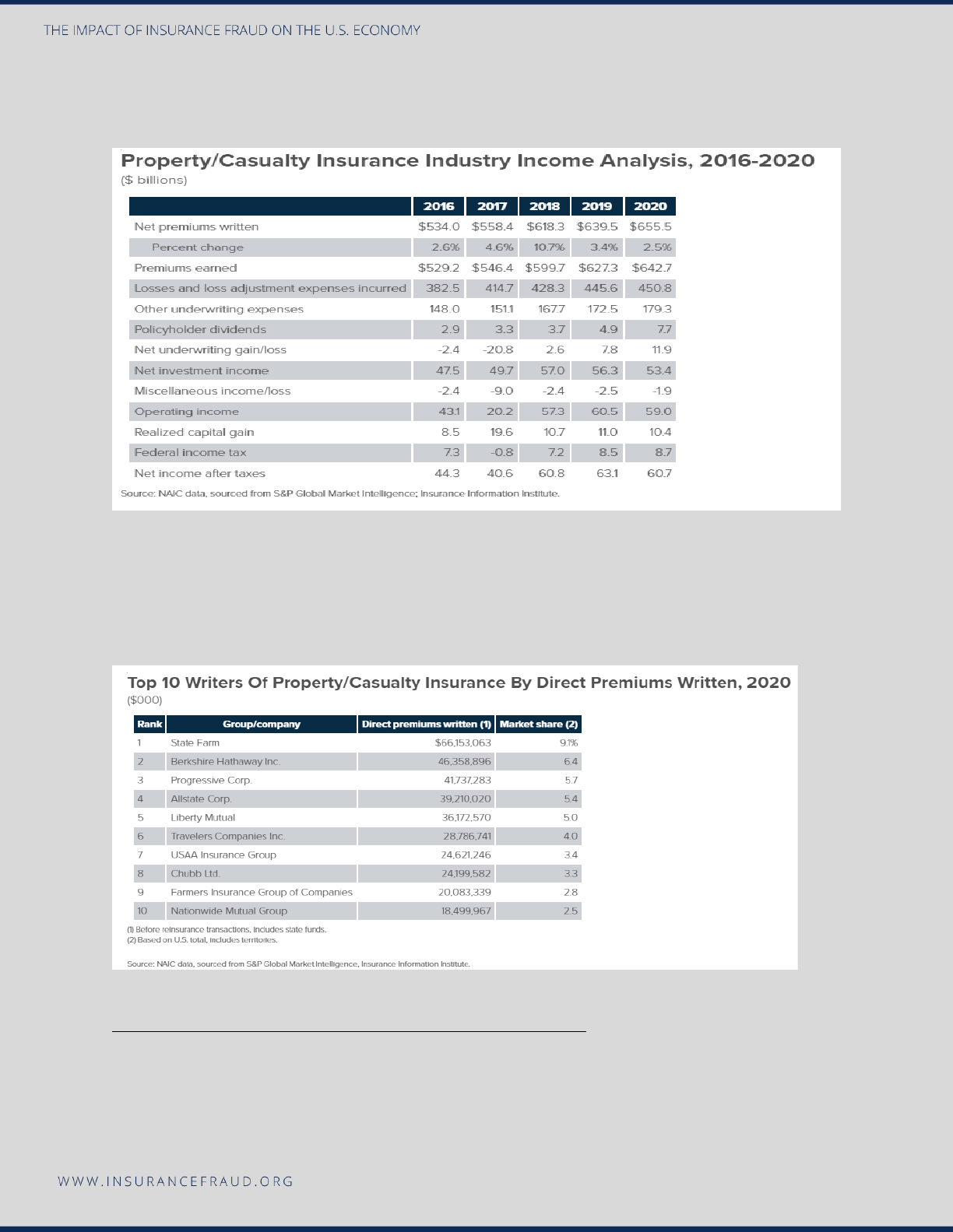

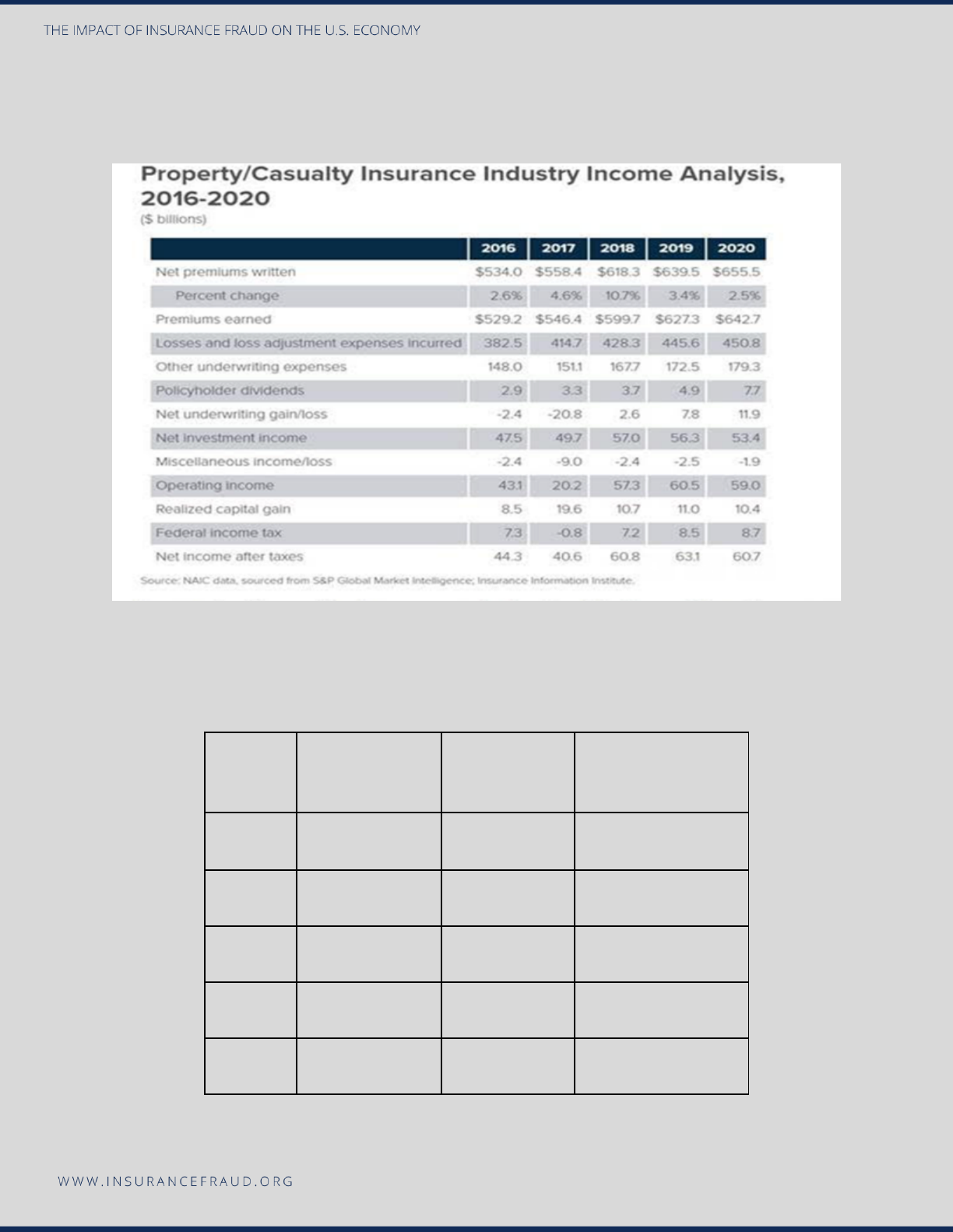

The following three visuals reveal interesting statistics on the property and casualty

industry in the United States.

The following graph shows direct premiums of property and casualty insurance in the

United States from 2004 to 2020 (in billion U.S. dollars).

Source: Statista 2021

7

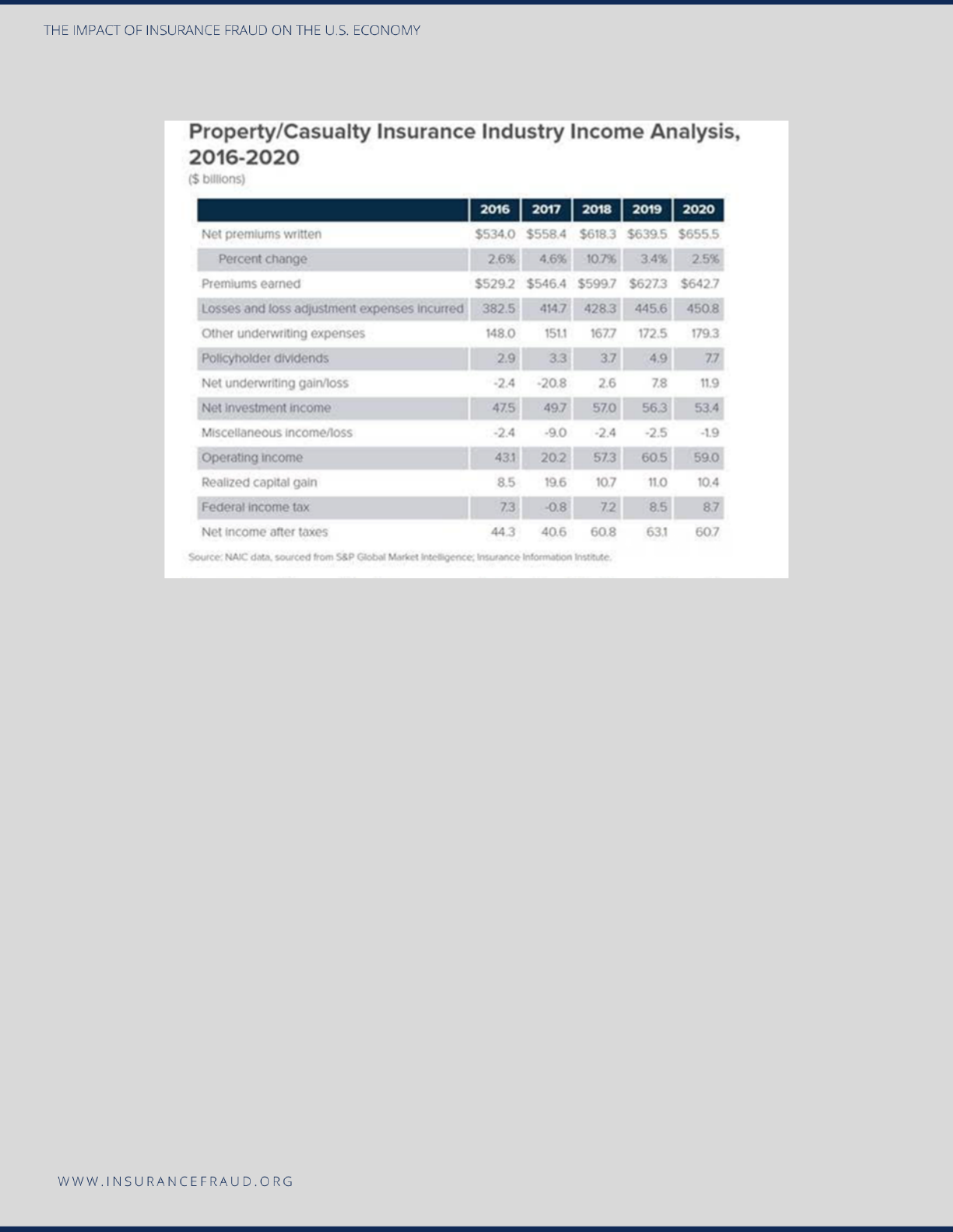

The following table shows a high-level property and casualty insurance industry

income analysis of 2016-2020 in billion U.S. dollars.

Source: Insurance Information Institute. (2021). Facts + Statistics: Industry overview.

https://www.iii.org/fact-statistic/facts-statistics-industry-overview

The following table shows the direct written premiums of the top 10 property and

casualty carriers in the U.S. in billion U.S. dollars.

Source: Insurance Information Institute. (2021). Facts + Statistics: Industry overview.

https://www.iii.org/fact-statistic/facts-statistics-industry-overview

b) Existing data pertaining to property and casualty fraud costs.

8

In addressing the current cost of fraud in the property and casualty line of business,

multiple sources were considered to assist with locating a new monetary amount.

Considering the structure of this study was one whereby the research team was not

gathering new data through qualitative or quantitative methods, an extensive search

was performed to secure as many potential sources of existing data and monetary

estimates on the cost of property and casualty fraud that have already been

performed. The research indicated that there is inconsistency with the definition of

what specific lines of business are included in property and casualty insurance.

Therefore, to provide an accurate metric on the current cost of property and casualty

fraud, the research team took great effort in clearly investigating what specific lines of

business were used in any research study or publication that helped calculate the

current cost. This was done to ensure that there was not an overlap in lines of business

that would potentially skew the final data.

Accordingly, there were two lines of business that are oftentimes included in property-

casualty fraud; auto theft and workers’ compensation. For purposes of this study,

those two lines of business will be analyzed separately to create a more accurate and

precise final figure on the cost of fraud. The research team removed those two lines of

business from this property and casualty cost and will focus on those separately to

provide a more accurate metric.

Auto theft is a type of fraud that is traditionally included in property and casualty fraud

and for the purposes of this study, the research team decided to analyze auto and

home theft as an entirely separate line of business. Therefore, there will be no auto and

home theft statistics included in this cost estimate for property and casualty fraud.

Workers’ compensation fraud is sometimes included in property and casualty fraud;

however, for the purposes of this study, the research team focused on workers’

compensation as an entirely separate line of business. Therefore, there will be no

workers’ compensation cost included in this property and casualty metric.

Regarding existing research and cost estimates for property and casualty fraud,

several sources were identified. The Federal Bureau of Investigations (n.d.) estimates

that insurance fraud (non-health) is estimated at more than $40 billion annually. *The

Insurance Information Institute (III.org) makes the following statement on its website:

“In the late 1980s, the Insurance Information Institute interviewed claims adjusters and

concluded that fraud accounted for about 10 percent of the property/casualty (PC)

insurance industry’s incurred losses and loss adjustment expenses each year. Using

that measure, in 2019 and 2020 P/C fraud would amount to $38 billion each year. The

figure can fluctuate based on line of business, economic conditions, and other

factors.”

9

*The III did not specify exactly how they derived at this figure, but the WCCTF

estimates that they first took 2019 and 2020 incurred losses (Loss & LAE) and then

multiplied that figure by 10% (average percentage claim fraud). The chart below is a

visual representation of how the WCCTF believes they arrived at the $38 billion figure.

As quoted by the III (above) they explain that they used the 10% average percentage

claim fraud as it was based on a study that they performed in 1980 by interviewing

claim adjusters from the industry. The WCCTF found that the 10% the III utilized for the

percentage of fraud in claims was also consistent with independent private

consultation research studies the WCCTF has performed and is also a percentage that

is widely cited as credible by many leading anti-fraud organizations, such as the ACFE,

and the Coalition; thus, the WCCTF deemed 10% as a credible percentage to use as

the average percentage of fraud in claims as a basis for this current 2022 study.

Casualty fraud, which is a component of property and casualty fraud, was studied in

2015 by the Insurance Research Council (2015) which estimated that casualty fraud

accounted for between 15% and 17% of total claims payments for auto insurance

bodily injury in 2012. The study estimated that between $5.6 billion and $7.7 billion

was fraudulently added to paid claims for auto insurance bodily injury payments in

2012. Using a standard formula CPI index and adjusting for inflation, the new cost of

casualty fraud in current dollars would be estimated between $6.8 and $9.3 billion. All

of the data and figures that resulted from the previously stated analysis will be used as

a baseline as the study unfolds.

*The $40 billion statistics from the FBI was deemed one of the most credible to

estimate insurance fraud as they are one of the premier law enforcement agencies in

the world and accordingly maintain a robust research platform and have a vast network

to gather credible and accurate data. The WCCTF located research by several state

Year

Loss &

LAE

Fraud

(10%)

Incurred

Losses*

Fraud (IL)*

2016

382.5

38.25

323.595

32.3595

2017

414.7

41.47

350.8362

35.08362

2018

428.3

42.83

362.3418

36.23418

2019

445.6

44.56

376.9776

37.69776

2020

450.8

45.08

381.3768

38.13768

10

insurance organizations, but due to the fact that this research was not available

consistently for every state, this was deemed as an unviable source.

*The Insurance Information Institute was chosen as the second most reliable, credible,

and effective data source as the III is one of the most well-respected members of the

insurance industry. Since 1960, the III has been one of the most trusted sources of

data for consumers, the media, and professionals in the insurance industry and at its

core organizational function researches and publishes information, statistics, and data

on the insurance industry.

*The 2012 study that the Insurance Research Council performed was chosen as the

primary data source as the IRC has been providing the property and casualty industry

with robust research since its inception in 1977, and along with the III is considered

one of the top insurance research organizations. The WCCTF found little to no studies

specifically focused on casualty fraud and therefore this somewhat dated 2012 study

by the IRC was seen as the most effective data source for the purposes of this study.

c) Research teams’ calculation on the updated cost of property and casualty

fraud.

The WCCTF considered the results developed in section b above but also wanted to

explore opportunities to develop an entirely new metric. Regarding a reasonable

methodology to calculate the current cost of property and casualty fraud, the WCCTF

concluded that an accurate formula would be to begin with the Loss Adjustment

Expense (LAE) for each year and then extract 10% of that LAE figure to arrive at a new

estimated cost of property and casualty fraud. The Actuarial Standards Board (2022)

defines the Loss Adjustment Expense as the “cost of investigating, administering,

determining coverage for, settling, or defending claims even if it is ultimately

determined that the claim is invalid.” It is also known as “claims adjustment expense.”

Accordingly, the WCCTF utilized the LAE as circulated by the III (Insurance Information

Institute, 2021, Facts + Statistics: Industry overview) and then calculated the new cost

of fraud by multiplying LAE by 10%.

Figure 1 shows a visual of the 2016-2020 property and casualty industry metrics for the

U.S. The LAE that is the focus of this analysis is seen in the 4

th

row, titled: “Losses and

loss adjustment expense incurred.”

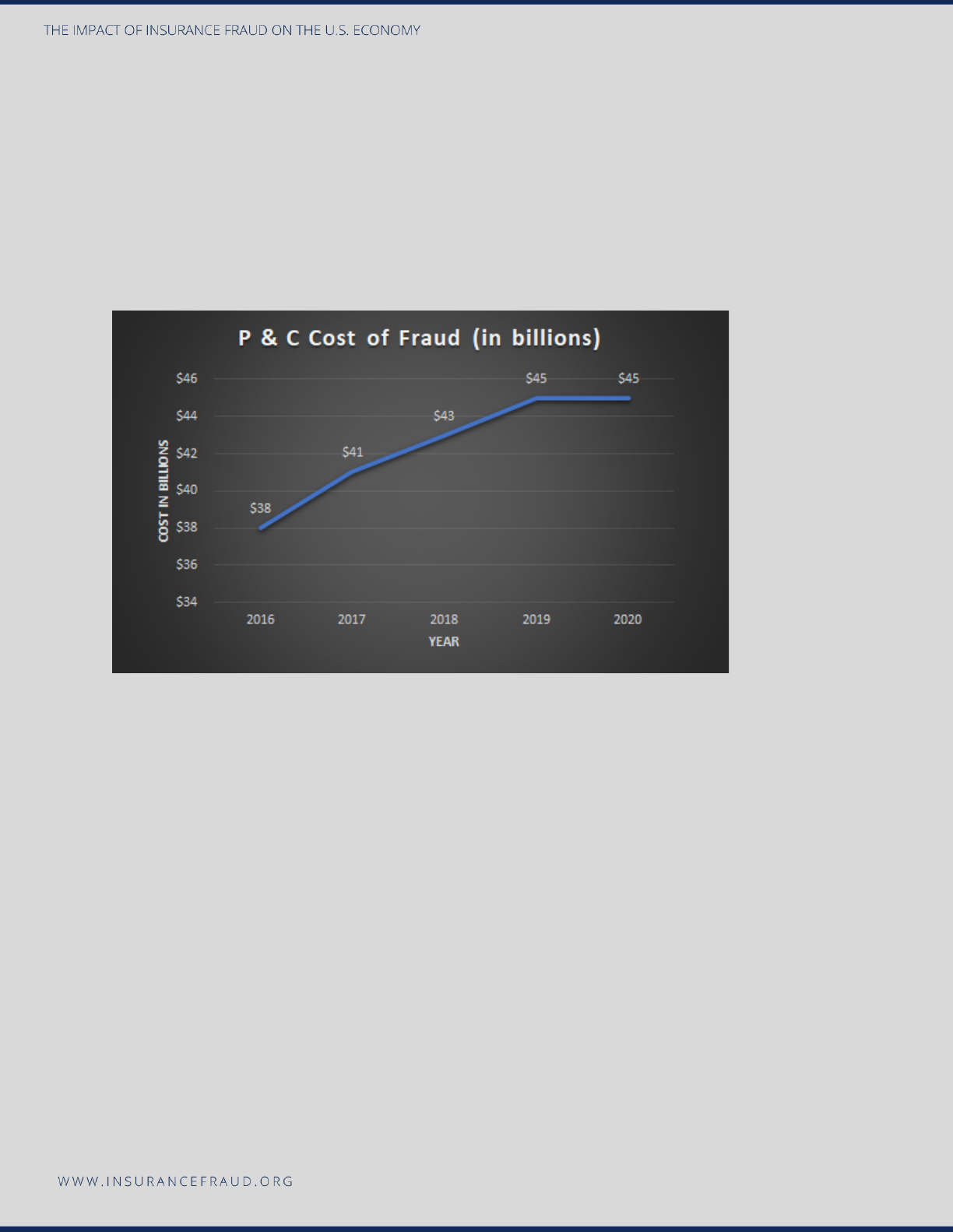

The final cost of property and casualty fraud was assessed from 2016 to 2020 by using

the LAE for each year and then multiplying that number by 10%. The results can be

viewed in two formats in Figures 2 and 3.

11

Figure 1

Source: Insurance Information Institute. (2021). Facts + Statistics: Industry overview.

https://www.iii.org/fact-statistic/facts-statistics-industry-overview

Figure 2: Cost of Property and Casualty Fraud 2016-2020 (in table format).

YEAR

LAE (in billions)

FRAUD (10%)

COST (in billions)

2020

450.8

10%

$45

2019

445.6

10%

$45

2018

428.3

10%

$43

2017

414.7

10%

$41

2016

382.5

10%

$38

12

Figure 3: Cost of Property and Casualty Fraud 2016-2020 (in graph format).

In conclusion, as indicated in a visual format in Figures 2 and 3 above, the WCCTF

estimates that the current cost of property and casualty fraud in the United States is

$45 Billion. When we consider the costs as revealed in section b from the FBI ($40

billion), III ($38 billion), and the IRC (between $5.6 and $7.7 in casualty fraud), the

current estimate of $45 billion appears credible and reliable.

Statement of No-fault

No fault insurance is required in twelve US states: Delaware, Florida, Hawaii, Kansas,

Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York, North Dakota, Oregon,

and Utah. In addition, no-fault policies are optional, but can be purchased in seven

other states: Arkansas, Kentucky, Maryland, South Dakota, Texas, Virginia,

Washington, and the District of Columbia.

There is no doubt that fraud exists in claims submitted under no-fault coverage,

whether in the form of staged accidents, medical provider fraud, or other schemes,

there is significant fraud exposure and the potential for serious financial loss. During

the initial data research phase of this study, it became immediately apparent to the

CSUG team that there is an overall lack of distinct reporting and recording of no-fault

insurance fraud in the United States. Most no-fault states include no-fault fraud as part

of their property and casualty metric, however, no-fault is not specifically defined and

calculated as a separate line item in that property and casualty metric in almost all

instances. Therefore, given the structure of the method that organizations currently

13

record and report fraud, and specifically how there is a lack of specific fraud recording

of no-fault fraud, it is not possible to develop a separate cost of no-fault insurance

fraud in the United States. However, it may be safely assumed that no-fault fraud is

included as part of the property and casualty final cost.

One of this study's key take-aways and recommendations is that no-fault states

specifically define and record no-fault insurance fraud as an entirely separate form of

fraud. Having an accurate and separate measurement of no-fault fraud will provide

insights into the cost of fraud that is ultimately passed on to the consumer.

Statement of the property and casualty metric.

The goal of this study is to increase awareness of the insurance fraud problem by

circulating a new and impactful cost of fraud and also serve as a starting point to

create specific calls to action for all involved in anti-fraud efforts to take additional

steps to modify and enhance our existing fraud reporting. As identified in the

“Statement of No-Fault” text above, there are significant gaps in the reporting of

property and casualty fraud. During all phases of research and data gathering in

regards to property and casualty fraud, it was extremely challenging to determine what

specific data was gathered when the research team located a data source. In almost all

of the instances, the term “property and casualty” was used very regularly in data

sources and articles, but there was never any specific breakdown of what specific

coverages were included. These gaps in reporting are significant opportunity areas for

the insurance industry to develop new protocols. As stated earlier, no-fault fraud needs

an entirely separate line item for reporting and the same is true for all forms of auto

insurance fraud. Most carriers and states capture auto insurance fraud as part of their

property and casualty measurement, and accordingly, auto insurance fraud is included

in the present study under the property and casualty figure. This study has identified a

significant gap in reporting related to auto insurance fraud; the research team

recommends that companies and states specifically define what exactly is included in

their definition of property and casualty statistics and record and report by the type of

coverage, such as no-fault (1st party coverage), auto property and casualty, fire

property and casualty, casualty (3rd party), etc… as this will provide deeper insights

into the impact of each specific area.

Workers’ Compensation

a) Introduction to the problem:

Workers' compensation insurance is accident coverage that is paid by employers. If an

employee is injured on the job, the employee may receive benefits to cover medical

bills, rehabilitation costs, and lost wages. Some policies even provide a death benefit.

14

Workers’ compensation insurance only applies if the employee is injured while

performing the duties of the actual job. Workers’ compensation systems vary from

state to state, thus there are many different systems in place in the United States,

creating challenges in regard to measurement, research, and collaboration.

Workers’ compensation fraud is defined as “a completely fabricated injury, or a

legitimate injury that is exaggerated by an employee to claim additional money.” There

are many legal definitions of workers’ compensation fraud, but the most widely used

definition (Insurance Council of Texas, 2022) states:

“Workers’ compensation fraud occurs when someone willfully makes a false statement

or conceals information in order to receive workers’ compensation benefits or prevents

someone from receiving benefits to which they might be entitled.”

Some examples of workers’ compensation schemes may include, overstating injuries

or limitations, concealing records that could be detrimental to a claim, claiming an

injury sustained on the job when it occurred elsewhere, and working “under the table”

while collecting temporary disability benefits.

One of the most challenging aspects of workers’ compensation fraud is that it is not

considered a high-profile crime; most individuals are not even aware that workers’

compensation scams are even a crime. Fraudulent workers’ compensation claims are

very damaging to businesses as they create a negative impact on a company’s bottom

line, revenue, and culture. Workers’ compensation fraud is not limited to employees,

there is also a significant amount of fraud that occurs from employers themselves in

the form of misclassifying workers and other policy misrepresentations to reduce the

premium amount that the employer actually pays to the insurer. Medical provider fraud

is the third area of fraud in workers’ compensation. This occurs when unscrupulous

medical providers overbill and bill for services not rendered.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (2022), it costs employers an average of

$957 per year per worker to provide legally required workers' compensation coverage,

which accounts for about 1.2 % of the total average employee compensation costs

incurred by employers. The average cost is $915 per worker in the private sector and

$1,186 per worker in state and local governments. When we look at the disturbing

trajectory of fraud in workers’ compensation, we also see an emerging, highly

disturbing pattern. As an example, Texas reported 99,850 workers’ compensation

claims in 2020, a significant increase from 73,628 in 2019 (Texas Department of

Insurance, 2022).

15

There are instances when a company feels justified to issue a workers’ compensation

denial. Research shows (Business Insurance, 2018) that claim denial rates increased

from 5.8% to 6.9% between 2013 and 2017.

The top 10 most common reasons for claim denial were:

● No medical evidence of injury.

● No injury per statutory definition.

● Reservation of rights, which is an insurer’s notification to an insured that

coverage for a claim may not apply.

● Pre-existing condition.

● Idiopathic condition

● Intoxication or drug-related violation.

● Non-work-related stress.

● Failure to report an accident promptly.

● The injured person doesn’t meet the statutory definition of an employee.

● Misrepresentation.

Below are several interesting visuals on workers’ compensation insurance as published

by the Insurance Information Institute (III). These provide some framework for this

challenging line of business.

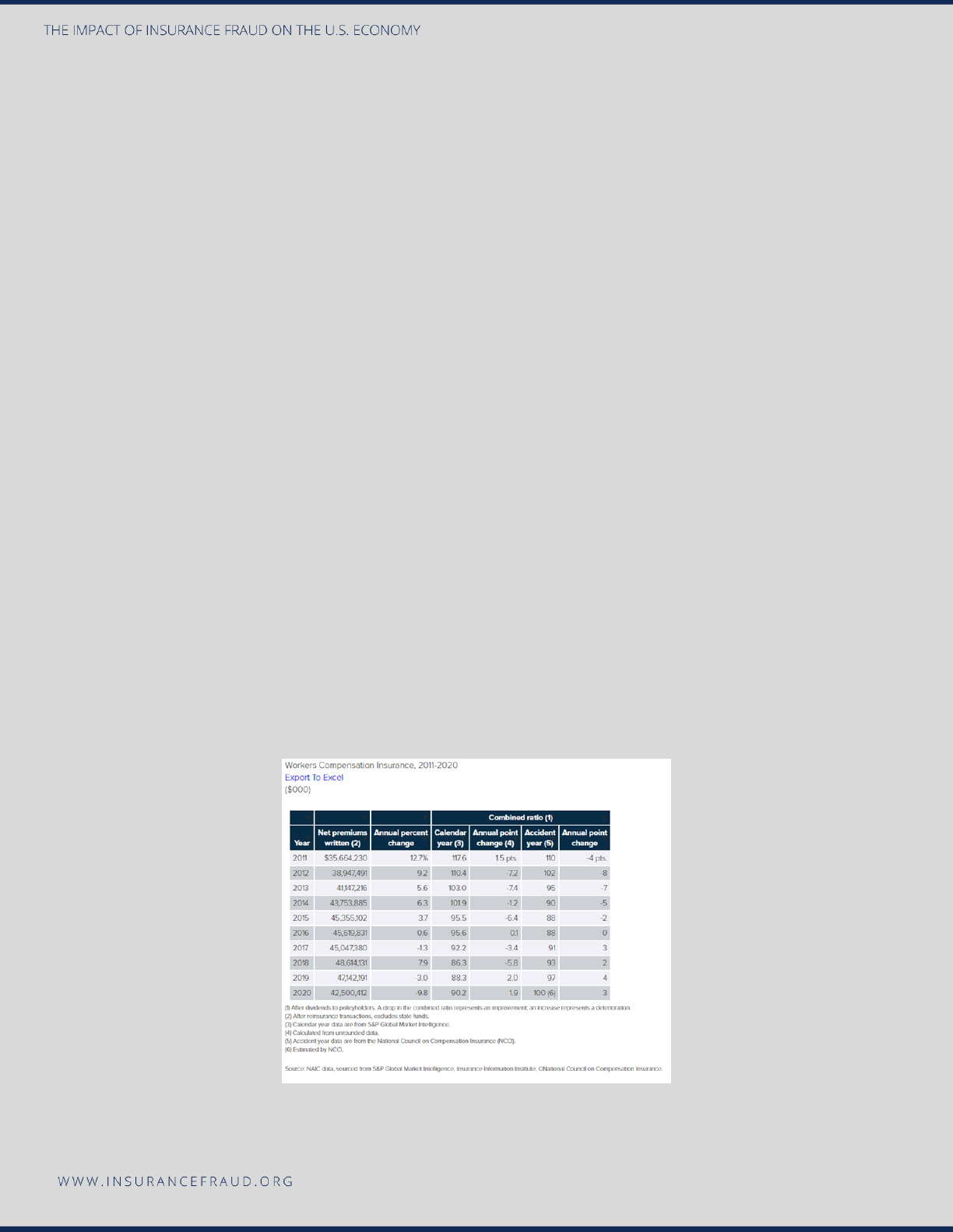

Figure 4 below shows interesting statistics on workers’ compensation insurance dating from 2011-2020.

It is interesting to note the pivot point starting in 2019 when the Net Written Premiums began to decline

from a steady growth since 2011.

16

Source: Insurance Information Institute. (2021). Facts + Statistics: Workplace Safety/Workers Comp.

https://www.iii.org/fact-statistic/facts-statistics-workplace-safety-workers-comp

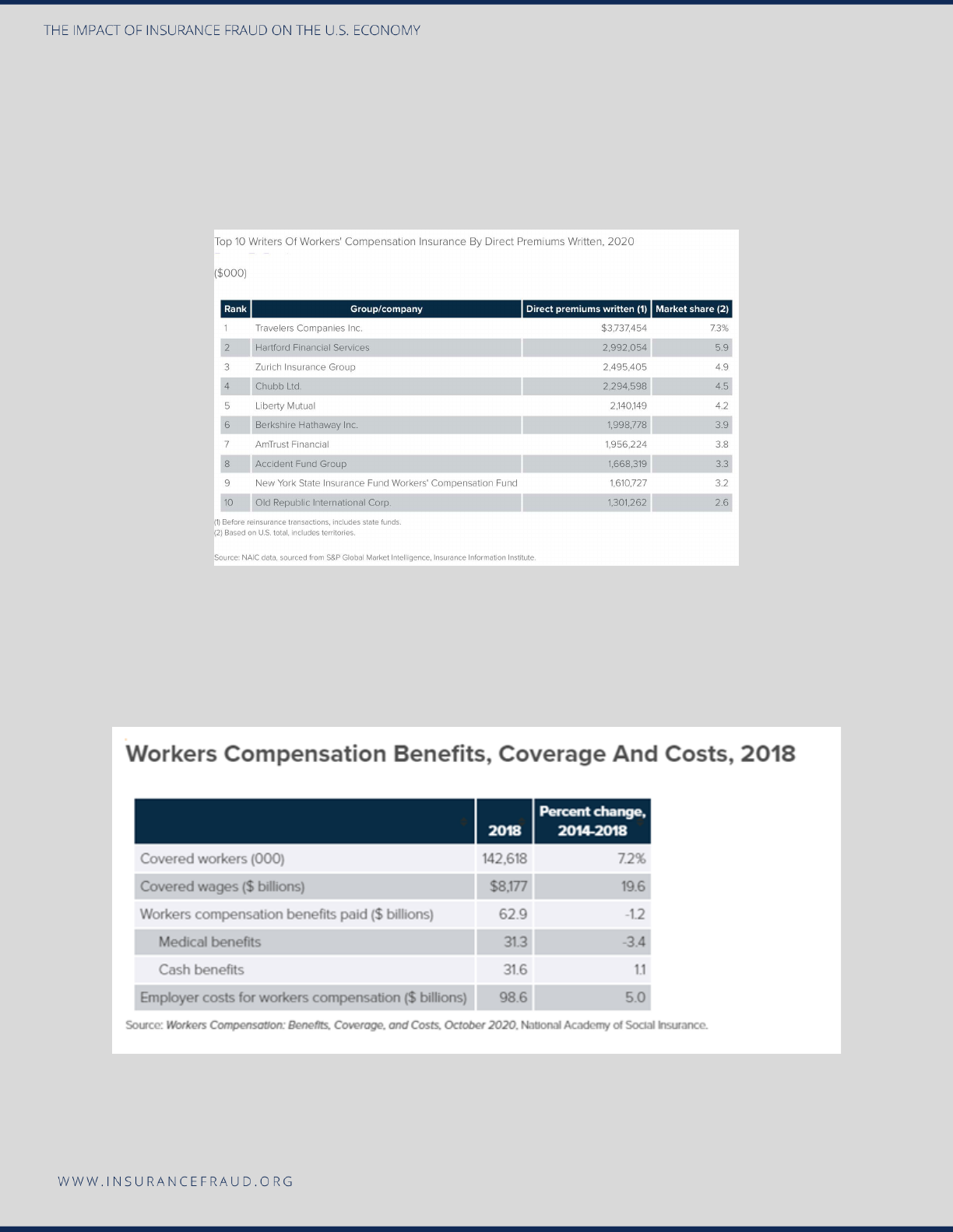

Figure 5 below shows the 2020 top 10 workers’ compensation insurance carriers by Direct Premiums

Written. As seen below, these 10 carriers comprised 43.6% of the entire market share of workers’

compensation premiums.

Source: Insurance Information Institute. (2021). Facts + Statistics: Workplace Safety/Workers Comp.

https://www.iii.org/fact-statistic/facts-statistics-workplace-safety-workers-comp

Figure 6 below shows the coverage and costs of workers compensation benefits in 2018. This chart

provides a nice indicator of the significant money that is involved in this type of coverage.

Source: Insurance Information Institute. (2021). Facts + Statistics: Workplace Safety/Workers Comp.

https://www.iii.org/fact-statistic/facts-statistics-workplace-safety-workers-comp

17

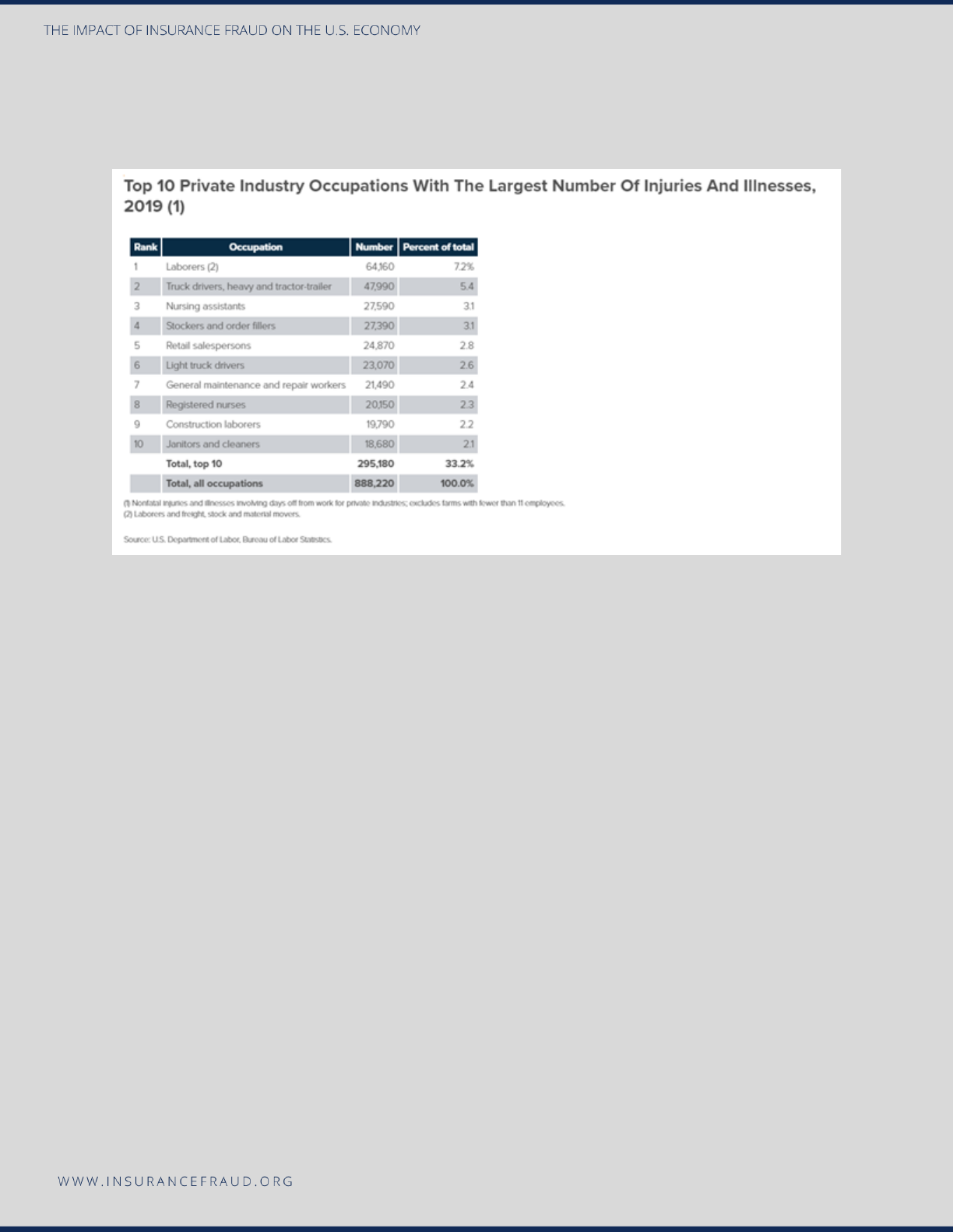

Figure 7 below shows the top 10 occupations that had the highest number of injuries and illnesses in

2019. From an underwriting and counter fraud standpoint, these occupations could serve as a basis for

red flag development and/or higher risk assessment.

Source: Insurance Information Institute. (2021). Facts + Statistics: Workplace Safety/Workers Comp.

https://www.iii.org/fact-statistic/facts-statistics-workplace-safety-workers-comp

b) Existing data pertaining to workers’ compensation fraud cost.

The WCCTF conducted a thorough review searching for existing research available on

workers’ compensation fraud costs. The WCCTF uncovered an extremely credible

research study being performed by the Coalition Against Insurance Fraud’s Workers’

Compensation Fraud Committee. *The WCCTF spoke directly to the committee and

the researchers of the study and reviewed all aspects of the project, including the

methodology and metrics, and deemed that this study was credible and accurately

represented the current state of workers’ compensation fraud. Accordingly, the

WCCTF determined that this 2022 Coalition study will serve as the main resource of

workers’ compensation fraud costs for purposes of this current 2022 study.

*The workers’ compensation statistic that the Coalition Against Insurance Fraud

publishes was deemed as the most credible source as the Coalition has been

supporting the insurance industry with research, advocacy, and support since its

inception in 1993. The Coalition is one of the most well-respected in the anti-fraud

community and provides robust services to consumers, the media, and insurance

organizations.

18

The following excerpt is from the Coalition's Workers’ Compensation Task force and

its research:

The Coalition's Workers Compensation Fraud Task force continues its work of

calculating a new figure that quantifies the amount of comp fraud taking place in the

U.S. Led by Co-Chairs, Dominic Dugo, and Gene Donnelly, the pair has assembled a

multi-disciplinary collective of experts in the field of WC to tackle the assignment of

updating the decades-old $7B estimate. Excluding self-insureds, the committee has

come up with a preliminary estimate of $34B in WC fraud divided between premium

and claim fraud. The committee examined a number of recent studies and reports to

ascertain the value of premium fraud. They also reached out to a number of experts and

academics to capture the cost of claim fraud. Dr. Michael Skiba, PhD and Department

Chair of Criminal Justice at Colorado State University Global, estimated a 16% fraud

rate in the claim volume based on research with dozens of carriers. Based on the 2020

written premium, and using the 16% number, the estimated amount of fraud in WC

claims is

$9B and $25B of premium fraud

. The Committee wants anyone with relevant

expertise or access to authoritative reports/information on fraud in the WC system to

share any information that may better inform their working estimate of $34B. If you have

questions about the committee's methodology or would like to participate in the effort

to update the WC figure, please contact Dominic Dugo at [email protected]g.

c) Research teams’ calculation on the updated cost of workers’ compensation

fraud.

The 2022 Coalition research project focused on two areas of workers’ compensation

fraud to determine their final figure; premium fraud and claim fraud. In analyzing

workers’ compensation claimant fraud it was determined using a base of 2020 written

premiums and multiplying that metric by a 16% fraud rate. A.M. Best provides a direct

written premium in 2020 of $56,225,576,000, which served as the baseline premium

metric. Prior studies performed by the WCCTF resulted in strong indications that 16%

of all workers’ compensation claims are suspicious, thus the use of the 16% figure in

this cost formula. Once written premiums ($56,225,576,000) were multiplied by the

16%, the final result was $8,996,092,160, appropriately rounded to $9 billion as the

final cost of workers’ compensation claimant fraud in 2020.

Workers’ compensation premium fraud was determined by first developing a cost of

fraud in the state of California and then using census data to predict the cost of fraud

countrywide. The baseline used was a $3 billion estimate that was derived by Frank

Neuhauser of the University of California Berkeley who performed a study on the

Underground Economy and Payroll Fraud. The Coalition’s Workers’ Compensation

Task Force used the $3 billion figure and then assumed California's population is 12%

19

of the total United States population (based on 2019 Census Data), the formula was

developed to determine the final cost. According to the United States Census data, in

2019, the U.S. population was 328 million and California was 39.5 million; thus,

California occupies 12% of the total U.S. population.

$3 billion (fraud in California) x 8.3 (California is 12% of the USA population), translates

into a metric of 100 divided by 12 = 8.3. Thus $3,000,000,000 x 8.3 = $24.9 billion

premium fraud in the United States.

The WCCTF, therefore, concludes that workers’ compensation claimant fraud totaled

$9 billion plus $25 billion in premium fraud, for a grand total of $34 billion in workers’

compensation fraud in the United States.

Premium Fraud

a) Introduction to the problem:

Premium fraud also referred to as premium leakage, is a very significant area of

insurance fraud, but is very difficult to assess due to the difficulties when trying to

determine policy misrepresentation on policies. Premium fraud can occur at almost all

points in the policy process, from signing up for a new auto policy to making policy

changes to an existing policy. Policyholders are motivated to misrepresent policy

information since premiums can cost less or more depending on facts that are

provided in the policy application; thus, enticing policyholders to misrepresent certain

facts on their policies in favor of lower premiums. During the initial policy application

process, an insured has the opportunity to misrepresent almost every item covered,

such as drivers, vehicle use, garaging locations, etc. After the policy is in force, the

policyholder can also engage in activity and fail to disclose it to the insurance company

for fear of raising their premium. Some of these activities would include moving to a

higher premium area, allowing a new driver to operate a vehicle, increasing the mileage

driven of a covered vehicle, etc. In addition to this challenge, insurers themselves are

pressured to write policies due to the highly competitive market in that they operate.

This pressure could result in insurers writing a bad risk, which will bring in premiums at

the onset but will be extremely costly to the insurer in the long term due to the high

propensity for fraud in these higher-risk policies.

There are many indicators and common red flags related to premium fraud; the

following are examples of some of these red-flag indicators:

Residency.

• Policy zip code and policyholder area code are in different areas.

20

• Insured is employed a significant number of miles from the policy address.

• Accident is more than a few miles from the policy address.

• Insured is reluctant to meet appraiser/adjuster/investigator at the policy address

and prefers a work location, coffee shop, and the like. This may indicate that

he/she does not reside there.

• Insured agrees to meet the appraiser/adjuster/investigator at residence address

but needs more than a reasonable amount of time to get to the location. Again,

this may indicate that the policyholder does not reside at the address.

• Insured uses a PO box as his or her primary mailing address.

• Insured cannot produce documents that show his or her name and the policy

address—documents such as utility bills, pay stubs, tax returns, or credit card

bills.

Vehicle mileage driven.

• Insured is reluctant to release mileage information via phone or in person.

• Insured avoids appraiser/sales agent/investigator physically viewing the vehicle.

• CARFAX or other database check reveals a significant number of miles in a

short period of time. This may indicate potential commercial use.

• Accidents occurs with multiple passengers that are not related or acquainted

with the insured. This may indicate that the insured uses the vehicle for

commercial or livery use, and potentially the mileage is misrepresented.

Other miscellaneous premium red flags would be as follows:

• Insured pays cash for the premium.

• If insured pays via check, the checks are starter checks.

• Re-employment, the insured is very vague about his/her job duties.

• Premiums seem very high for the insured’s socioeconomic status.

Red flags indicators that can be communicated to first notice of loss report taker:

• Insured provides a PO box.

21

• Multiple people making the loss report.

• Agent documentation indicates that the insured had a higher-than-normal

number of inquiries to the agent prior to loss.

• Insured is hesitant to release personal information and is generally

uncooperative.

• Insured is overly aggressive for a settlement and could also threaten contacting

supervisors, state consumer bureaus, attorneys, etc.

• Insured seems unusually familiar with insurance terms.

• Multiple recent changes in policy coverage, including the coverage that

specifically affects the claim being reported.

(Skiba, 2017)

b) Existing data pertaining to premium fraud cost.

The WCCTF performed an in-depth search canvassing for current research on

premium fraud. After performing this comprehensive search, it was discovered that

there is little to no research performed in the area of premium fraud. The WCCTF’s

extensive search resulted in one study that was performed in 2017 on premium fraud

that was deemed credible and will serve as the foundation for this LOB in this 2022

study. Premium fraud in auto insurance was the focus of a study performed by Verisk

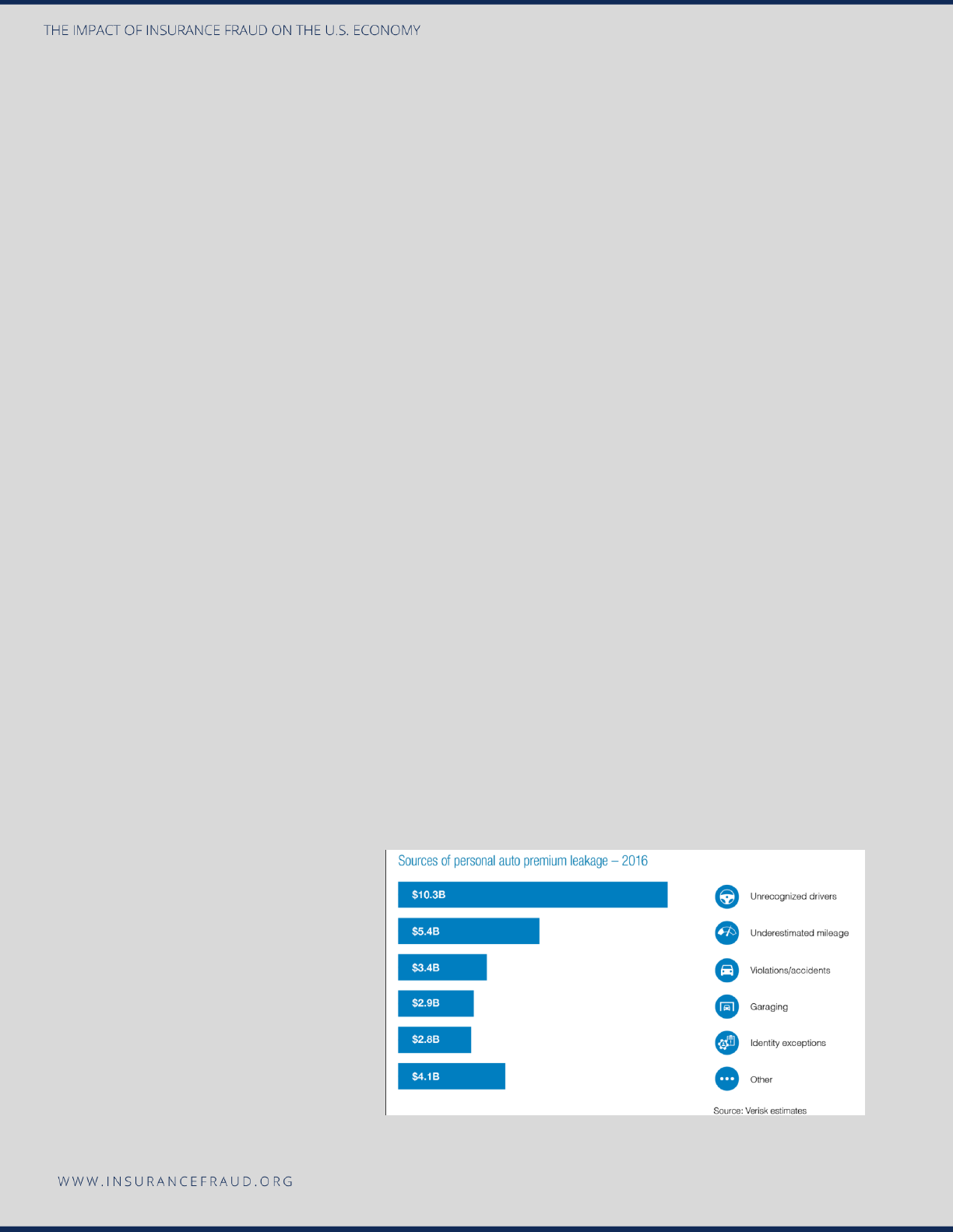

in 2017, which estimated that $29 billion was lost due to premium fraud. *Their

calculation included unrecognized drivers, underestimated mileage, violations,

garaging, and identity exceptions. Significant growth in the use of technology platforms

to write policies (non-face-to-face) makes it easier for an insured to misrepresent items

on their policy. As seen below in Figure 8, their study revealed the following sources of

leakage.

Figure 8: Sources of Personal Auto

Premium Leakage

Source: Verisk, 2017.

Due to the lack of other

research uncovered during the

investigation of this LOB, and

the credibility of this study, the

2017 Verisk study will be the

22

primary source of information for this current 2022 study.

*As noted, the Verisk 2017 study was deemed the most effective for the purposes of

this research project. The WCCTF reviewed the Verisk study parameters (copied

below) and accordingly, approved of this methodology as a credible source of data.

“Two Verisk research initiatives support the majority of findings for this Innovation

Paper. The 2016 Verisk Auto Insurance Premium Leakage Survey explored insurers’

concerns, programs, and plans regarding premium leakage. The response represented

58% of private passenger auto insurance premiums. Verisk also conducted a client

analysis for 82 insurers split evenly between standard and nonstandard. The research

combined Verisk’s RISK:check® predictive analytics model that identifies potentially

fraudulent applications with additional data from more than 3 million policies (2.1

million standard, 1 million nonstandard).”

c) Research teams’ calculation on the updated cost of premium fraud.

The 2017 Verisk study will serve as the basis for premium fraud for the purposes of this

study. The Verisk study concluded that in 2017 the cost of premium fraud was $29

billion. If we use a standard Consumer Price Index (CPI) conversion of $29 billion from

2017 to January 2022, we receive a new 2022 cost of fraud of $31.6 billion.

The WCCTF sought a second source to cross-check the final $31.6 billion estimate

derived using the Verisk foundational estimate. To establish a second metric, the

WCCTF used a formula based on the estimated percentage of premium fraud as

established by Reinsurance Group of America (RGA) and then divided that percentage

into the 2020 net written premium for the U.S. A global study performed by RGA in

2017 assessed premium fraud at a rate of 5.9 percent *(Reinsurance Group of America,

2017, Global Claims Fraud Survey). Considering the total net written premium for 2020

($655.5 billion-Figure 9) we derived a formula of $655.5 billion x 5.9 %, which resulted

in a figure of $38.7 billion. When we cross-check this figure of $38.7 billion with the

Verisk figure of $31.6 billion, we can ascertain that both costs are of course different,

but they are within the same range for the WCCTF to be comfortable releasing a new

estimated figure based on these two numbers.

23

Figure 9: Total Net Written Premium 2016-2020 (in billions).

Source: NAIC data, sourced from S & P Global Market Intelligence: Insurance Information Institute.

Regarding the final cost of premium fraud in the U.S., if we take the two figures of

$31.6 and $38.7 billion, and then average these two numbers together, the new figure

for the cost of auto premium fraud in the United States is $35.1 billion.

*The RGA study metric of 5.9% was based on premium fraud in the Americas and did

not isolate The United States from the final 5.9% figure. Despite this shortcoming, the

WCCTF felt that the 5.9% was still the most accurate measure to serve as a baseline

for this project. Regarding the methodology, the RGA conducted an online survey in

September and October 2017 of 27 insurance carriers.

Healthcare Fraud

a) Introduction to the problem:

According to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (2020, CMS Office of the

Actuary Releases 2019 National Health Expenditures), healthcare spending in 2019

made up nearly 18% of the country’s Gross Domestic Product, totaling $3.8 trillion.

Nearly all of this spending was paid for by insurance. Health insurance has grown in

utilization and popularity across America for the last 100 years when insurance became

24

more widespread following World War I. In 2010, the federal government passed

groundbreaking legislation in the Affordable Care Act. This regulation aimed to give

access to insurance to people that may not have had it prior, and as a result, a large

percentage of Americans are currently covered by health insurance, and most of our

$3.8 trillion annual GDP is paid by health insurance. In a post-Affordable Care Act,

post-Medicaid Expansion America, the United States Census Bureau (2020), estimates

that 92% of people in the U.S. have some form of health insurance. Using those two

figures, an estimated $3.5 trillion in healthcare costs are paid by insurance annually.

Altogether, this makes healthcare a unique and attractive target for fraud, both

because of a large amount of dollars available, and because so much of the spending

is paid by insurance rather than by the individual receiving services.

Insurance fraud schemes can take many forms in healthcare. These schemes are

found in all areas of healthcare, including hospitals, pharmacies, clinics/doctor’s

offices, long-term care facilities, home health services, pharmaceuticals, medical

devices, and durable medical supplies. In some cases, providers bill for services that

were never rendered, which can include billing for services to patients who are

deceased, or who have never seen the provider submitting the claim. Other schemes

involve “upcoding,” or submitting a claim for a service more complex and with a higher

reimbursement rate than the service that was rendered. Upcoding can include billing

for a high quality of medication or supplies, or by inflating complexity. Most provider

visits include an evaluation and management of service. This service can be

reimbursed at multiple rates depending on how complex the patient’s care is and how

difficult evaluating the patient and managing their condition is. Determining the correct

level of complexity is highly subjective, and creates an environment where providers

often determine what level is appropriate on their own. This level of autonomy creates

a large opportunity for fraud.

More complex schemes involve the practice of “unbundling,” where a provider will bill

for each component of a service individually rather than submit a single billing code

that covers all services, as required by some insurance companies. Often a billable

service will include lab work, follow-up, visits, or other auxiliary services that are

supposed to be included in a single rate. Fraud can be committed by submitting claims

for all of the services individually rather than accounting for the included services in the

initial code. Insurances, including both Medicare and Medicaid as well as most

commercial plans, require that a service be medically necessary to be reimbursed. The

provider submitting the claim is often key in determining whether or not the service is

necessary. This allows the provider who will directly benefit from additional services to

manipulate the situation to fraudulently bill by making false statements about a

25

patient’s condition to show medical necessity, including fabricating diagnoses and

misrepresenting the patient’s true conditions.

Healthcare fraud can also be committed by the patient. Medical identity theft has been

becoming more and more common, with uninsured or underinsured persons

presenting to a healthcare provider a name, identification, and insurance information

for a different person. Occasionally, fraud is committed through willing “card sharing”

rather than identity theft. This occurs when a willing person shares their health

insurance information with a family member or friend and helps them impersonate the

insured person when seeking care to get the insurance company to pay for the care

provided to a non-covered person.

b) Existing data pertaining to healthcare fraud cost.

No major commercial health insurance companies report fraud estimates, and national

organizations that do gather this information do not publicly publish it and declined

WCCTF requests for this information. The WCCTF approached approximately 10

carriers and received denials for access to the information they gathered. The WCCTF

located three separate sources of data that were deemed credible for this study. The

National Healthcare Anti-Fraud Association (2019), *is a premier organization in

healthcare fraud and estimates that between 3%-10% of health insurance spending is

lost to fraud nationwide; if we assume the higher 10% metric, fraud costs in health care

could surmount to $300 billion. The WCCTF then used CMS’s 2020 data which shows

$3.8 trillion in total healthcare spending and 2019 United States Census data showing

92% of people in the United States carried health insurance, and calculated as follows:

$3.8 trillion x 92% = $3.5 trillion is paid annually for health insurance claims. CMS data

(as explained in detail in the next lob section on Medicare and Medicaid) shows that

Medicare and Medicaid spending in 2020 totaled $1.5 trillion, meaning the remaining

$2 trillion was paid by commercial insurance plans.

*The NHAFA is seen as the leading healthcare fraud fighting organization in the United

States healthcare industry. They were founded in 1985 and are a private-public

partnership that is comprised of over 100 insurance carriers, law enforcement, and

regulatory agencies. Also affiliated with the NHAFA is the NHCAA Institute for

HealthCare Fraud Prevention, which was established in 2000 and is a separate

educational organization that provides both education and training to anti-fraud health-

care personnel. Accordingly, the WCCTF deems the NHAFA as a highly credible and

reliable source of healthcare research and data.

c) Research teams’ calculation on the updated cost of life insurance fraud.

26

As outlined above, considering the limitations of available statistics (both publicly and

directly from private health carriers) on health care fraud, the WCCTF felt that the most

accurate method to derive at a healthcare fraud metric would be to utilize the data

secured from the NHAFA on fraud percentage (3%) and CMS on total health care

spending ($3.5 trillion). The WCCTF applied the estimated 3% of dollars spent to be

lost to fraud as established by the NHAFA to the $3.5 trillion healthcare expenditures

as established by the CMS. This would suggest total healthcare claims fraud costs all

insurers, including Medicare and Medicaid, $3.5 trillion x 3%= $105 billion annually.

To arrive at an accurate metric on healthcare spending, we must extract from that $105

billion, the amount of fraud in relation to Medicare and Medicaid fraud. Referring to the

next line of business section on Medicare and Medicaid, we derived at a final figure

(averaging AARP and USGOA data) of $68.7 billion dollars to Medicare and Medicaid

fraud. Subtracting Medicare and Medicaid fraud from the total figure leads us to

conclude that fraud costs $36.3 billion per year ($105 billion - $68.7 billion).

Medicare and Medicaid

a) Introduction to the problem:

Medicare and Medicaid are government programs that pay healthcare expenses for

vulnerable populations. Medicare is a federal program focused on elderly and disabled

persons. This is a population that would have less access to traditional health

insurance because private health insurance is often provided through an employer, and

individuals in these populations tend to either be retired or unable to work because of

their disability. Medicare recipients pay an insurance premium and often have other

out-of-pocket costs such as deductibles and coinsurance. The premium is subsidized

by government funds and the provider network and pricing agreements are managed

by the government.

Medicaid is a state-run program that provides access to families living near the poverty

level. Medicaid recipients generally do not pay a premium or out-of-pocket costs. All

costs are paid by the government, which also manages the provider network.

Medicare and Medicaid fraud has a lot in common with traditional healthcare insurance

fraud. Fraud schemes can include billing for services not rendered, upcoding,

unbundling, and providing unnecessary services. Differences are reflected in the nature

of the services provided and the nature of the recipients. Medicare and Medicaid

recipients are more vulnerable to fraud than the general population. Elderly and

27

disabled persons are at higher risk of being fraud victims because they are generally

less involved in the decisions behind their care and may not be as likely to pay close

attention to their bills or may struggle to understand their bills. Since Medicaid

recipients often do not have any cost-sharing, they are less likely to pay attention to

any aspect of billing, making them a larger target. The Department of Health and

Human Services Office of Inspector General considers some services providers to be

at higher risk for committing fraud. Hospitals and physicians are generally considered

lower risk, with Home Health Agencies and Durable Medical Equipment providers

being considered high risk. Because they are more likely to be dealing with life limiting

diseases and decreased functionality, Medicare and Medicaid patients are more likely

to receive services from high-risk providers than the population covered by traditional

insurance. The government also spreads more resources on investigating and

pursuing fraud over private, commercial, insurance companies. This suggests that

Medicare and Medicaid would experience more fraud than commercial insurance

companies.

b) Existing data pertaining to Medicare & Medicaid fraud cost.

The WCCTF conducted an exhaustive search canvassing for metrics on Medicare and

Medicaid fraud and found an incredibly wide range and inconsistent results, such as

metrics of $60 billion annually from the University of Southern California Center for

Elder Justice (2021) to $134 billion from the Center for Medicare and Medicaid

Services (2020) and even groups such as the Center for to the National Conference of

State Legislatures (2022) concluded that fraud in Medicare and Medicaid is nearly

impossible to measure. The CMS was seen as a very credible source by the WCCTF,

but after deep analysis into the $134 billion figure they derived at, it was decided to

refrain from including the metric in the final analysis. CMS themselves estimated $134

billion (2020), annually in improper Medicare and Medicaid claims, however, they point

out that not all improper claims were necessarily fraud. The WCCTF arrived at the $134

billion figure by adding up the 2020 Improper Payments from FFS, Part C, Part D,

Medicaid, and CHIP dollars from the chart in the citation above from the CMS website.

This $134 billion number includes waste and abuse, which may be unintentional, such

as a misunderstanding or a disagreement about when there is an honest, good-faith

question regarding medically necessary. This figure also follows Office of Management

and Budget Office guidance that any claim unsupported by documentation is assumed

to be improper rather than undetermined. It was therefore decided to refrain from

including the CMS number of $134 billion as part of this study.

The WCCTF scoured for other sources and located two other highly credible sources

that will be utilized for this line of business. The American Association of Retired

28

Persons (AARP), referencing United States General Attorney Jeff Sessions, estimates

that CMS pays $1,000 in fraud claims per member, or roughly $60 billion (2018). *

The United States Government Accountability Office (USGOA) puts the number a little

higher, at $77.4 billion (2019). *The WCCTF derived at $77.4 billion by referring to the

report, which states $36.2 billion for Medicare Fee-for-service/FFE and another $41.2

billion for Medicaid, which summed together, total $77.4 billion.

*AARP is the nation’s largest non-profit organization representing individuals over 50.

Having roughly 40 million members in the United States, it is considered the most

credible and robust organization focusing on matters of that age group. Accordingly,

this organization is known to provide highly detailed and accurate research and

reporting on topics related to individuals over 50, such as Medicare and Medicaid.

*The United States Government Accountability Office is a legislative branch

government agency that provides auditing, evaluation, and investigative services for

the United States Congress. Their primary function is to investigate and monitor federal

spending and performance. As they are the top agency in the United States that

monitors federal spending, they are an ideal resource to provide data and research for

this study.

c) Research teams’ calculation on the updated cost of life insurance fraud.

The WCCTF calculated a final number for Medicare and Medicaid fraud by taking an

average of the AARP ($60 billion), and the USGOA ($77.4 billion) figure, $60 billion +

$77.4 billion = $137.4 billion divided by 2 = $68.7 billion. Although some sources do

not consider Medicaid to be insurance as there is technically no risk sharing, the

general population considers it to be a form of insurance, and it functions from a billing

perspective similarly to Medicare and other commercial insurers. Therefore, the

WCCTF believes Medicare and Medicaid fraud should both be included in the total

amount.

Life Insurance Fraud

a) Introduction to the Problem:

Life insurance fraud is deliberate deception committed by an insured or insurance

agent to gain a financial advantage. Applicants, policyholders, third-party claimants,

and professionals who provide services are all potential fraud sources. Misrepresenting

life insurance policy information, tampering with another person’s policy, and fake

deaths, are among the common frauds. Life Insurance fraud is one of the most serious

29

problems facing insurers, insurance consumers, and regulators. Its existence not only

increases the cost of insurance but also threatens the financial strength of insurers and

negatively affects the availability of insurance. Insurance fraud encompasses a wide

range of illicit practices and illegal acts involving intentional deception or

misrepresentation. Some of the most common forms of life insurance fraud include:

● Lying on an application. This involves adjusting, or even withholding valuable

information, such as any medical conditions.

● Forgery. A common scheme is when someone other than the policyholder will

change a beneficiary.

● Fake policy. Fake agents sell fake policies that do not exist and pocket the

money.

● Faked death. In these instances, people try to collect for someone who is still

alive or never existed.

● Murder. When a beneficiary plans to kill a policyholder and pocket the payout.

● Pocketing premium. An agent pockets the premium payment instead of

forwarding it to the company.

Life insurance policies also involve a contestability period, that is, the time frame in

which an insurer can deny a claim for material misrepresentation and fraud. This period

varies by state, but it is generally one to two years. Research by the Reinsurance

Group of America (2017) reveals that 20% of life insurance policies are rescinded by

insurance companies.

b) Existing data pertaining to life insurance fraud cost.

The WCCTF performed a robust search looking for current data on life insurance fraud

and unfortunately, very limited information was revealed. The WCCTF searched every

potential platform in search of research on life insurance fraud statistics including open

source, direct industry contacts with the III, NAIC, FBI, the Coalition, ACFE, IASIU, and

academic libraries. As a result of that exhaustive search only one study that was

conducted in 2017 by the Reinsurance Group of America (RGA) was found. All other

sources that were located that focused on life insurance fraud made reference to the

2017 RGA study, confirming that the RGA study was the only research study

completed focused on life insurance fraud.

To understand the life insurance fraud problem the RGA surveyed 25 insurance

carriers, conducted informational interviews among insurance carriers, held information

gathering discussions at the 2016 RGA Annual Fraud Conference, and conducted their

internal research of the claims experience. Based on that method, the RGA reported

that they estimate life insurance fraud to cost approximately $10-20 billion each year.

30

The RGA further states that 1%-3% of all life insurance claims are either investigated

for fraud or misrepresentation, or they are denied outright.

c) Research teams’ calculation on the updated cost of life insurance fraud.

In considering the research revealed in section b above, it was determined that a new

figure for the cost of life insurance fraud would be necessary. Although the 2017 RGA

study added insights and was the most cited in terms of life fraud, the methodology

was based on several survey instruments, and even though this could be a very

credible source of information, without knowing the details of the survey instruments,

the research protocols, the sample, etc., the WCCTF felt that a new cost was needed.

To arrive at a new formula for life insurance fraud, the WCCTF looked for data on the

total life insurance benefits and claims paid in past years. A very credible and accurate

source was uncovered when the WCCTF located data published by the III. *(Insurance

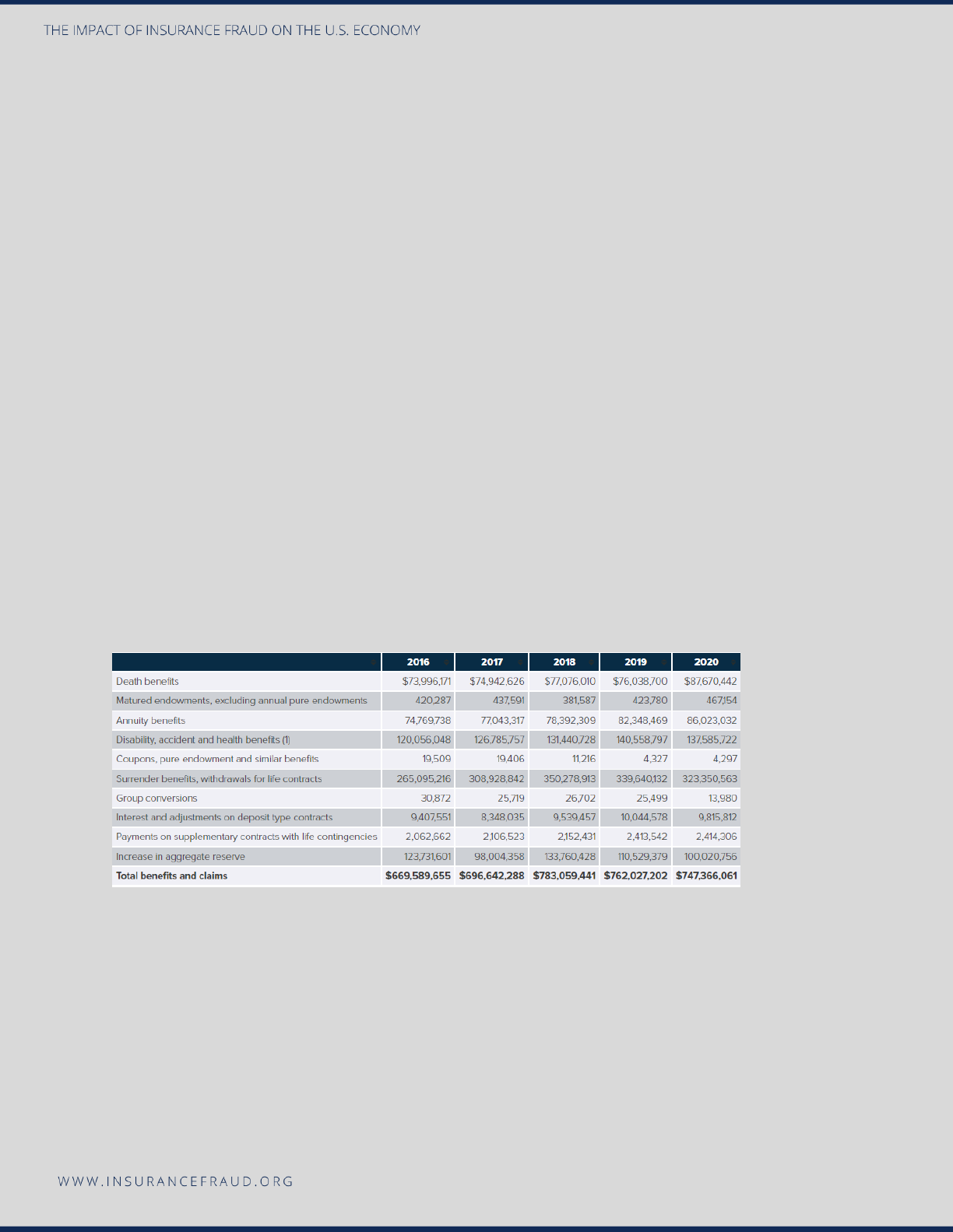

Information Institute, 2021, Insurance Fact Book Payouts). As seen by Figure 10 below,

a recent study by the Insurance Information Institute (III) showed life insurance benefits

and claims reached $747.4 billion in 2020. The amount includes death benefits from life

insurance, annuity payments, disability payments, and other payouts. It is interesting to

note when analyzing data in this form that life insurance benefits have slowly declined

since 2018.

Figure 10: Life Insurance Benefits and Claims 2016-2020

Source: Insurance Information Institute, 2021, Insurance Fact Book Payouts.

Key fraud organizations such as NICB, III, the Coalition, NAIC, and IASIU, widely

circulated the figure of 10% as the key percentage of claims that are fraudulent.

Accordingly, the WCCTF will propose a new cost of life insurance fraud using the total

benefits and claims payout as indicated by the III in Figure 10 above and then use the

metric that 10% of all life claims are fraudulent as a baseline. Using this formula, if the

life insurance benefits and claims payout was $747.4 billion in 2020, and we estimate

that approximately 10% of that figure was fraudulent we would derive at a new cost of

31

$747.4 billion x 10% = $74.7 billion. Therefore, the 2020 estimate of life insurance fraud

in the United States is $74.7 billion.

The increasing number of life insurance frauds not only increases costs for the

companies but also leads to inflated premiums, which is felt by consumers. Therefore,

it is necessary to have a proper risk management framework to curtail or minimize life

insurance fraud. A life insurance company’s commitment to fraud control will be met

by identifying the opportunities for fraud and implementing risk avoidance, its

prevention, and procedures for its minimization in the day-to-day system of operations.

*As already noted in the property and casualty line of business section earlier, the

Insurance Information Institute was chosen as the most reliable, credible, and effective

data source as the III is one of the most well-respected members of the insurance

industry. Since 1960, the III has been one of the most trusted sources of data for

consumers, the media, and professionals in the insurance industry and at its core

organizational function researches and publishes information, statistics, and data on

the insurance industry.

Disability Insurance Fraud

a) Introduction to the Problem:

Disability fraud involves making a false statement, providing incorrect information, or

withholding information to collect benefits (individual or group). There are many forms

of disability fraud, including; faking a medical issue to be declared disabled, continuing

to collect payments after the individual has recovered, receiving benefits while working

another job, usually “off the books”, exaggerating a medical condition to meet the

disability threshold for collection and inflating income on a Social Security Benefits

application to increase payout.

In reviewing the current literature related to disability fraud, there appear to be many

inconsistencies in its definition and measurement. Some sources include disability in

workers’ compensation fraud, some consider it an entirely separate line of business,

and yet others define it separately, but segment it as being fraud against private

carriers and the Social Security Administration. It is also readily labelled “improper

payments” by the Social Security Administration. Due to these inconsistencies and the

wide variety of definitions, parameters, costs, and statistics being circulated, the

WCCTF decided to focus on Social Security Disability fraud as the primary area of

study as these statistics are well defined in the literature.

32

b) Existing data pertaining to premium fraud cost.

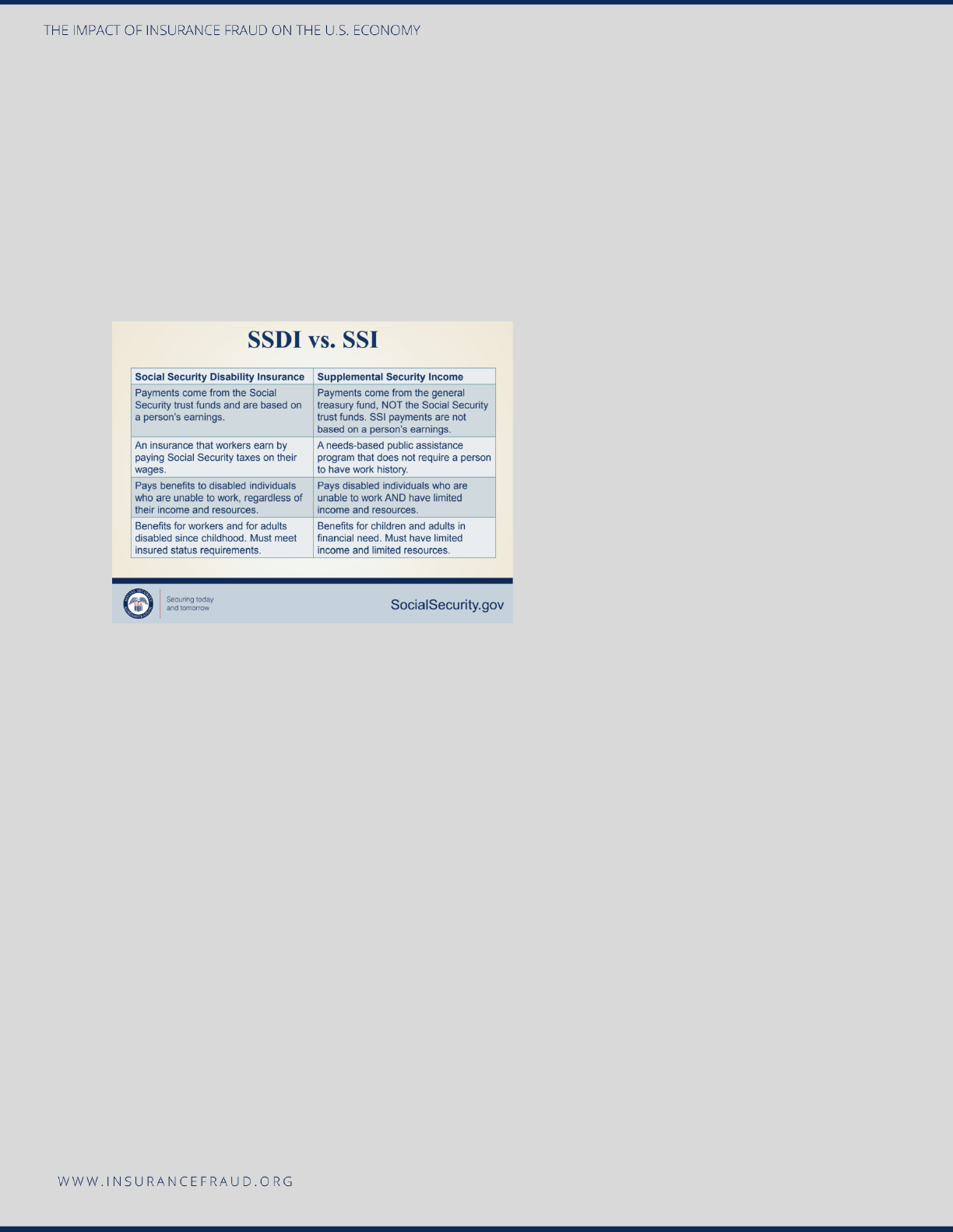

The Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) and Supplemental Security Income (SSI)

programs offer assistance to individuals that are disabled. SSDI pays a benefit to an

injured party or family member if you are an eligible worker and have paid Social

Security taxes on your income. SSDI will reimburse individuals with disabilities who

have limited income. The table below (Figure 11) shows the highlights of the difference

between SSDI and SSI (Social Security Administration, 2022).

Figure 11: Comparison of SSDI vs. SSI

Source: Social Security Administration, 2022.

As previously mentioned, the WCCTF

will focus on Social Security

Disability fraud, or Improper

Payments, as the focal point for

developing a cost current 2022 cost

of disability fraud. The WCCTF

performed an exhaustive search for

credible and accurate data pertaining

to disability insurance and located

several interesting sources but decided for the purposes of this study to utilize data

from the most seminal organization in this area, the Social Security Administration

(SSA). As the SSA is the top branch of the United States government that oversees life

insurance and therefore the data and research they publish is an ideal fit for purposes

of this study.

The Social Security Administration (SSA) considers payments to be improper, “…if they

result from a mistake in computing the payment, its failure to obtain or act on available

information, a beneficiary’s failure to report an event, or a beneficiary’s incorrect

report”. The SSA considers improper payments to comprise of both under and

overpayments; underpayments when they mis-calculate benefits, and overpayments

when they pay someone more than they are due. The SSA estimated that in 2019, a

total of $7.9 billion was paid in total improper payments (Social Security Administration,

2020).

c) Research teams’ calculation on the updated cost of life insurance fraud.

As the SSA data is incredibly reliable, robust, and accurate, the WCCTF focused on

data published by the SSA as the basis to develop the new cost of disability fraud in

33

the United States. The SSA estimated that in 2019, $7.9 billion was paid in improper

payments, that is, both overpayments and underpayments (defined in section b above).

As underpayments are payments that the SSA makes as a result of improper

calculation, and potentially an error on behalf of the SSA, it was decided that because

these types of payments are not necessarily fraudulent, the WCCTF will refrain from

including underpayments in the final cost of disability fraud. In other words, the

WCCTF will only focus on overpayments as these payments can be precipitated by

insured and beneficiary misrepresentation and fraud. We conclude that our new cost of